I have restarted the analyses since for about a fortnight with the new Melbourne outbreak. The logic behind these charts is that they fill an information gap. Official data sources only give historic data series, and mainstream media typically only give near term predictions based on opinion.

Chart update 19 July 2020

What’s new?

Today’s new number of cases, 381 as per the Australian Department of Health 19/7/2020 update, remains very consistent with the projections of the model. We are now ten days into the stage 3 restrictions (“lock down”) of Melbourne. I have some increasing concerns that I’ll describe in more details below in “my interpretation”.

Although it might not be so clear visually, the growth in new cases over the past week has not been consistent with “exponential” growth, which is what we often see early in an outbreak, especially if there is uncontrolled community transmission. This is in contrast with the growth in new cases in early July that fit very well within an exponential series.

My experience with this model from the March 2020 was that projections from early on in the epidemic tend to underestimate slightly in the short-term (days), and overestimate in the longer-term (weeks). This bias is something to keep in mind.

Note: the new daily charts are now in SVG (scalable vector graphics) format to improve their clarity at all resolutions.

Projection of new daily cases of COVID-19 with data up to 19 July 2020 (Day 10 after “lock down”)

What is this?

The image is a chart of the confirmed daily new cases of COVID-19 in Australia, with a projection for the next 2 weeks. The projection is made using a model by fitting the data since 1 June 2020 to a Gompertz equation using non-linear regression. The dark blue dashed line is the model estimate. The grey dashed lines are the 95% prediction intervals, with the values given at 7 and 14 days into the future. The blue gradations can be understood as the degree of uncertainty in the model projections.

“Gompertz” equation?

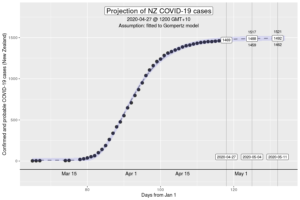

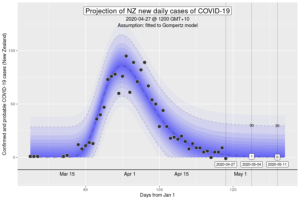

The Gompertz function is a type of sigmoid, or “S”-shaped curve. It’s been around since the early 19th century and was initially used to describe and model demographic mortality curves, and hence, well known to actuaries. The Gompertz function can also be used to accurately model biological growth (e.g., epidemics, tumour size, enzymatic reactions). Early in the pandemic, it was identified that it was useful in modelling cumulative cases of COVID-19 from the Chinese outbreaks (Jia et al. arXiv:2003.05447v2 [q-bio.PE]). My experience from the initial outbreak from earlier in the year is that this was also the case in Australia and New Zealand (for instance, NZ data below).

How have the model projections changed over the month?

The video demonstrates how the projections have evolved over time as new daily data have become available. This can give a better sense of where we are headed, given that the model cannot account for changes in context (e.g., policy changes, changes in testing rates, etc.)

My interpretation

The data over the past month is consistent that a new outbreak, with the growth in cases initially in the “exponential” phase. The growth was slowed down since that initial rapid growth. However, as outbreaks don’t really grow exponentially so at a certain level, this isn’t surprising. Gompertz models better describe the growth, but there is a lot of uncertainty in future projections from early data. In effect, it’s too early to call whether the daily new case count is going to “peak” soon (or possibly has peaked), or whether this is still consistent with ongoing community transmission in the Australian context, on the basis of the statistical model. For instance, if we look at the “peak” in the March-April outbreak in New Zealand, which likely occurred at around April 1 when analysed retrospectively, new case counts bounced up and down for a period of about one-and-a-half weeks around this date.

As such, there is reason to hope. Melbourne went into “lock down” at midnight at the start of 9 July 2020. Assuming that the outbreak is limited to Melbourne, we should expect to see the peak incidence of new daily cases after roughly a week. This was what occurred after the national “lock down” that started 23 March 2020, and this probably provides the best guide of what we might expect.

That said, we are now ten days into the Melbourne lock down. My personal expectation is that I would have expected to see some evidence of the model projections initially over-estimating as the actual new cases hit their peak, and then, the model “catching up” with the data and giving more accurate projections “down the hill” as new daily cases drop (see chart below). This is what we saw in the first wave. Below is a chart using the same methodology from during the period March to April. As a reminder, the first “lock down” started on 23 March 2020. Ten days after the lock down (i.e., analogous to today) was 2 April 2020. The projections of this chart are based on data up to and including 2 April 2020. As we are doing this from the “future”, so to speak, the actual case counts after 2 April 2020 are available as well.

Projection of new daily cases of COVID-19 with data up to 2 April 2020 (Day 10 after the first “lock down”) vs today’s projections (Day 10 after the Melbourne “lock down”)

As can be seen, by ten days after the first lock down, it is clear that the model identified that we had crossed the peak of new cases. In fact, the projections of new daily cases into early and mid-April ended up being quite accurate.

Notably, this chart from the first wave is very different from the projections today. The current July data continues to be consistent with the model projections, but there isn’t any suggestion that we’ve crossed the peak. This has me concerned that although the growth is clearly no longer exponential, current policies might not be sufficiently reducing transmission.

Although this sounds a bit grim, it should be noted that this is not the only interpretation. It might be that the impact of a policy like the “lock down” in the Australian context takes more than 10 days to become apparent. The first lock down that started 23 March 2020 was preceded by several weeks of escalating restrictions and a “private” lock down of sorts. This does not appear to have happened in Melbourne prior to the 9 July 2020 lock down.

The other big unknown is the degree of community transmission from people who have travelled from Melbourne to other parts of Australia in the past 2 weeks. If this has occurred, it is likely that we’ll start to see new outbreaks in other parts of Victoria and in the other states. There is an established cluster in South Western Sydney with ongoing new daily cases, that is of significant concern.

Want to know more?

Primary data source is the Australian Government Department of Health COVID-19 website for daily new cases. Analysis done using RStudio Cloud.

Today’s charts

Projection based on data up to 2 April 2020

Data: 20200427 – COVID_AU-world

R code: covid_au-world