I restarted the analyses from early July 2020 with the onset of the new Melbourne outbreak. The logic behind these charts is that they fill an information gap. Official data sources only give historic data series, and mainstream media typically only give near term predictions based on opinion.

Chart update 1 August 2020

What’s new?

Today’s new number of cases, 418 as per the Australian Government Department of Health 1/8/2020 update is somewhat lower than the projected estimate, and, is mostly consistent with the model. The very high new case counts in the preceding two days was not repeated today. Observed as a pattern over the past week, it would seem that a reasonable explanation is “lumpiness” in the reporting of the data, with the consistency in the underlying growth dynamics of the outbreak. That is, I am reasonably hopeful that the two days of high case counts do not represent a “new” outbreak.

We are now over three weeks into the stage 3 restrictions (“lock down”) of Melbourne, which started on 9 July 2020. According to the model, the peak in new cases is about one-and-a-half weeks away. I am concerned at how “wide” the peak appears. An implication of this is that if transmission suppression is not improved, new case counts may take a long time to lower even after growth has plateaued. On a cumulative case chart, this would appear as a period of relatively linear growth. If some of the policies commenced in Melbourne are effective at reducing transmission further (e.g., mandatory use of face coverings, and enhanced monitoring of home isolation/quarantine compliance), the model will be providing over-estimates. The trend in the changes in the model has been a lowering of estimates over the past week, though this has stalled in the past few days. This is best seen in the animation below.

My experience with this model from the March 2020 was that projections from early on in the epidemic tend to underestimate slightly in the short-term (days), and overestimate in the longer-term (weeks). This bias is something to keep in mind.

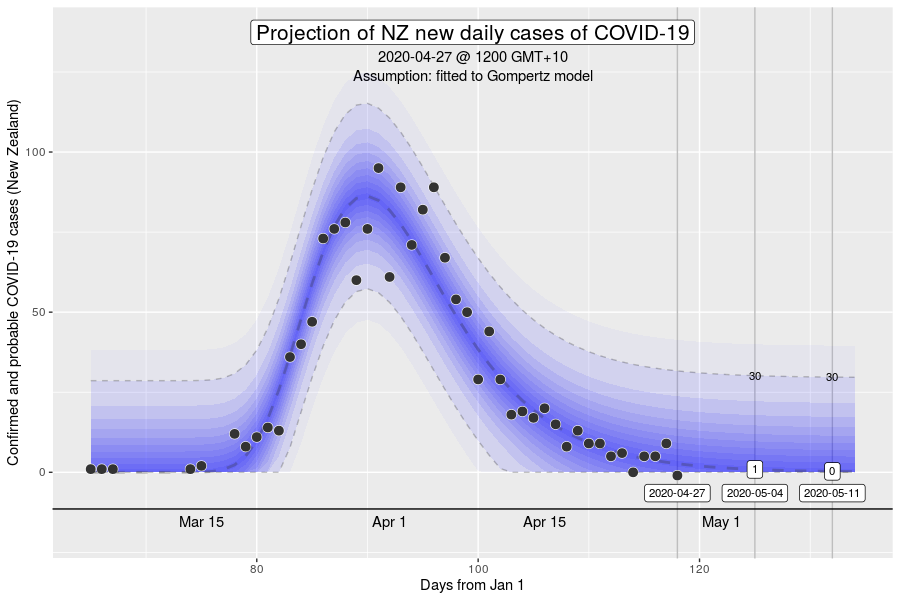

Projection of new daily cases of COVID-19 with data up to 1 August 2020

What is this?

The image is a chart of the confirmed daily new cases of COVID-19 in Australia, with a projection for the next 2 weeks. The projection is made using a model by fitting the data since 1 June 2020 to a Gompertz equation using non-linear regression. The dark blue dashed line is the model estimate. The grey dashed lines are the 95% prediction intervals, with the values given at 7 and 14 days into the future. The blue gradations can be understood as the degree of uncertainty in the model projections.

“Gompertz” equation?

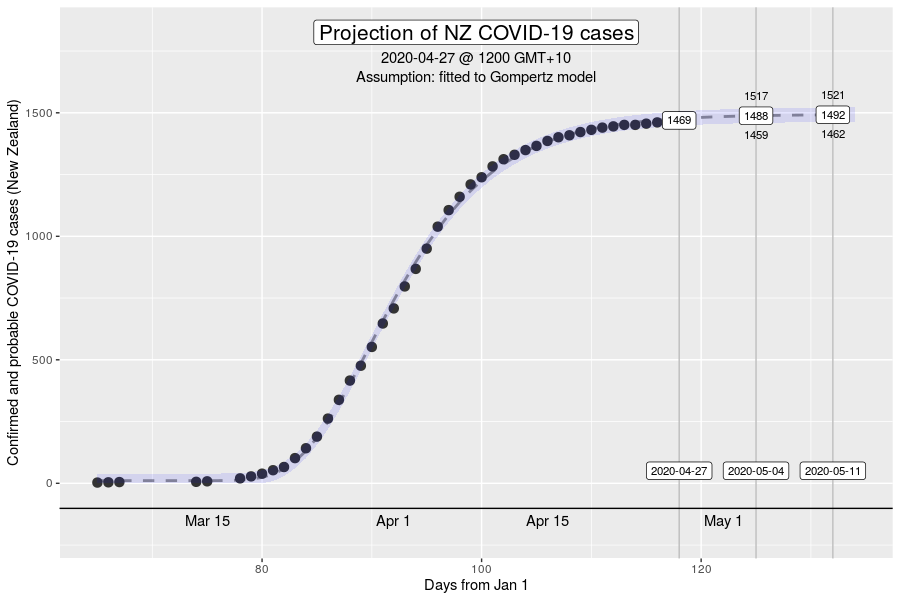

The Gompertz function is a type of sigmoid, or “S”-shaped curve. It’s been around since the early 19th century and was initially used to describe and model demographic mortality curves, and hence, well known to actuaries. The Gompertz function can also be used to accurately model biological growth (e.g., epidemics, tumour size, enzymatic reactions). I have chosen to use this model to help with creating insights as earlier in the pandemic, it was found to be useful in modelling cumulative cases of COVID-19 from the Chinese outbreaks (Jia et al. arXiv:2003.05447v2 [q-bio.PE]). My experience from the initial outbreak from earlier in the year was that this equation gave reasonable descriptions of Australian and New Zealand data (for instance, NZ data below).

How have the model projections changed over the month?

The video demonstrates how the projections have evolved over time as new daily data have become available. This can give a better sense of where we are headed, given that the model cannot account for changes in context (e.g., policy changes, changes in testing rates, etc.)

My interpretation

Thankfully, the shockingly high case counts from yesterday and the day before did not continue today. In the absence of news of a major new outbreak, or a reason to suspect a loss of control of transmission, my hunch is that the high counts (along with some unusually low counts) are related to structural effects in the reporting of the data (i.e., in the processes of identifying and testing). For example, in some (though not this) data, there are clear weekday-weekend patterns.

There remains concern with the daily number of cases in NSW at multiple locations across Sydney and the state. New daily numbers haven’t climbed in the past week, but also haven’t whittled away. I think the phrase “on a knife’s edge” has been used to describe the situation in NSW. Widespread testing and contact tracing is taking place, along with improving physical distancing adherence and use of masks. Hopefully, it will be enough.

More information about the “peak” in new cases

What does it mean to have reached the peak in new cases? Assuming that our suppression of transmission doesn’t become MORE effective after the peak, it’s important to recognise that it is not the “halfway point”, which might be the intuition. The peak in the “new cases” curve corresponds to the “inflexion point” on the S-shaped cumulative cases curve (e.g., the first chart of the NZ cases in the brief description on the “Gompertz equation”. Roughly, the peak in new cases occurs at 40% of the total cumulative cases in an outbreak. That means that at the time we hit the peak, we can expect another one-and-a-half times the number of cases so far in the outbreak, before it ends. The insight is that we must resist the psychological temptation to relax transmission control mechanisms simply because we “crossed the peak”.

Want to know more?

Primary data source is the Australian Government Department of Health COVID-19 website for daily new cases. Analysis done using RStudio Cloud using R version 4.0.2.